Food Loss and Waste country profile China

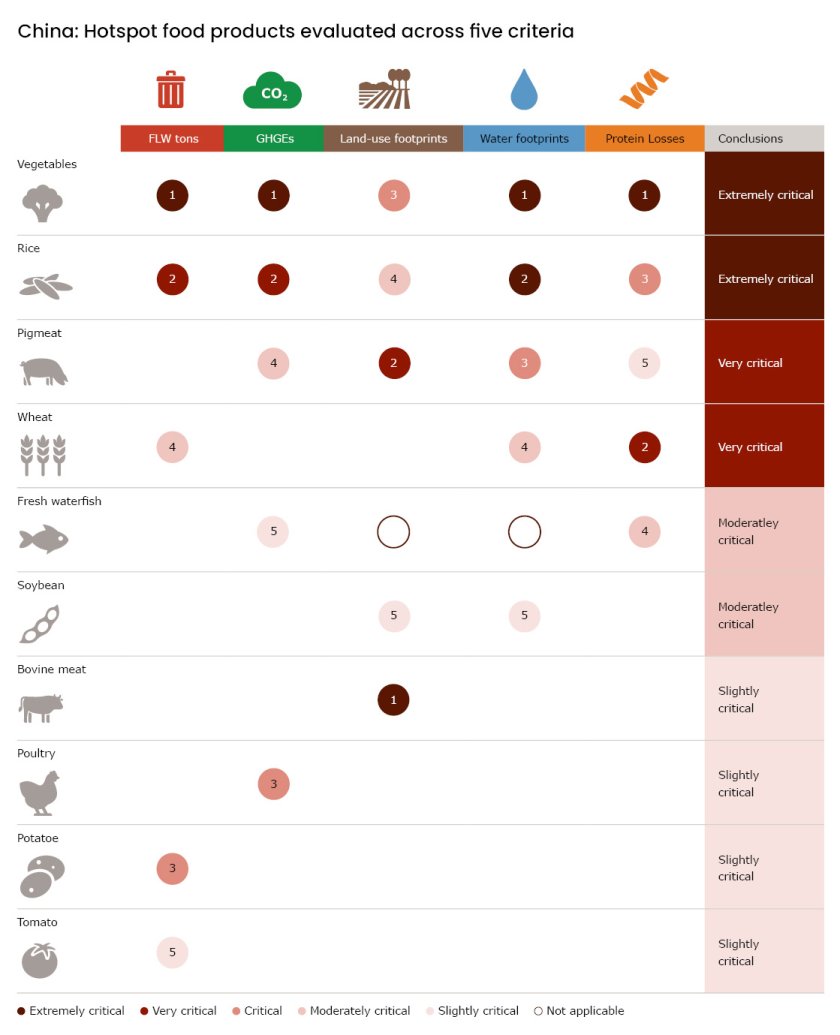

In China, vegetables and rice emerge as extremely critical hotspots, followed by pig meat and wheat.

Urgency and call for action on Food Loss and Waste (FLW) reduction

Globally, each year possibly as much as 30% of the food produced is being lost or wasted somewhere between farm and fork. Food Loss and Waste (FLW) accounts for around 8 to 10% of our global Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGEs). Approximately a 25% of all freshwater used by agriculture is associated to the lost and wasted food. 4.4 million km² of land is used to grow food which is lost or wasted. The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 12.3 calls to ‘halve per capita global Food Waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce Food Losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses’. With only 6 years to go, the world is far from being on track to achieve this target.

FLW, GHGEs, nutrition, land use and water footprint country profile China

Based on the country data modelling, estimates on FLW-associated GHGEs were retrieved for China and plotted with the FLW total tonnage to visualize the two components (Figure 1).

Food categories were ranked according to the production of FLW-associated GHGEs. For FLW, vegetables, rice, potatoes, wheat and tomatoes are the hotspots. The five hotspot products for FLW-associated GHGEs are: vegetables, rice, poultry meat, pig meat and freshwater fish. The category ‘vegetables, others’ has by far the highest FLW in weight as well as associated GHGEs, 100,000 and 79,000 tons respectively. For rice 46 million FLW tons induce 64 million tons CO2-eq. GHGEs.

Figure 2 presents the top 15 items with the

largest land-use footprints of FLW. Bovine meat, pig meat, vegetables, rice,

and soybeans rank the top five. Note that land use footprints do not apply for

aquatic products.

With respect to the water footprints of the FLW, vegetables, rice and pigmeat are the top 3 contributors followed by wheat and soybeans (Figure 3). Here also, the indicator ‘water footprint’ does not apply to aquatic products.

From another perspective, taking the percentages of FLW in relation to production percentages, potatoes and the four aquatic products are identified as the main hotspots showing average losses of 45% and 44% respectively along the chains (Figure 4).

Figure 6 shows the protein losses associated with FLW where vegetables, wheat, rice, freshwater fish and pig meat are the top five items. Finally, the food supply and FLW data were used to assess nutrient supply per capita in the Chinese population in relation to recommended nutrient intake (Figure 7). These are average numbers, and it is not likely that nutrients are evenly distributed across China. Hence, there will be parts of the population that suffer insufficiencies of calcium, iron and energy (carbohydrates, fat). From nutrition security perspective, efforts for mitigating FLW in soybeans, wheat, fish and rice chains would contribute the most to population nutrient gains (Table 1).

Overall conclusions and suggestions for the next steps

Figure 8 displays a comprehensive ranking of hotspot food products based on five criteria. While there are ten hotspot food products identified, a closer examination reveals notable variations in the ranking of them across the five criteria. Vegetables and rice emerge as extremely critical products serving as a hotspot for all five categories. Pig meat follows closely, positioned as a hotspot for four categories and also falls into the category of extremely critical products. In the next tier of hotspot products, wheat is classified as very critical hotspot product. Fresh waterfish and soybean are identified as hotspots for two product categories and are classified as moderately critical. Bovine meat, poultry, potato and tomato being identified among the top five products in one of the categories but not any of the other four categories and are therefore classified as slightly critical products.

It is suggested to develop FLW reduction actions, with synergy on GHGEs mitigation, nutrition, land-use and water footprints. The above analysis underlines that, if one considers sustainability in the context of these five indicators the greatest impact can be achieved by concentrating efforts on vegetables, rice, pig meat, and wheat compared to focusing on other food products.

Since the results are not on product level, it is not immediately clear, where to start your intervention. Our suggestion is to develop FLW reduction actions, with synergy on GHGEs mitigation, nutrition, land-use and water footprints, is to implement monitoring or/and gather primary data for hotspot-supply chains of the country. The results in this document guide stakeholders by focusing on the top five food (sub)categories in combination with the indicative results on FLW per supply chain link. To research interventions, it is necessary to go to product level, which can be based on production or trade data in the country. The next step is to identify business cases for FLW reduction. For this purpose, WUR’s EFFICIENT protocol and FLW cause and intervention tool can be used.